Eric Webb, “Home To Fork:

Victory Gardens in the Valley of Eden”

from World War II Sacramento

Home To Fork: Victory Gardens in the Valley Of Eden Author: Eric Webb Publisher: The History Press Date: 2018 ISBN: 9781467138086 Footnotes: in new window |

Business and civic leaders in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries promoted a unified vision of the Sacramento region. Steeped in the prevailing Romantic-era ideal of “rural virtue,” which lamented the effects of industrialization while simultaneously glorifying nature, these local boosters beckoned potential residents with elaborate portrayals of an agricultural and environmental paradise. Sacramento and its environs were a veritable Garden of Eden, they exclaimed, a place “where even Adam and Eve would feel at home.”178

Future landowners would find themselves surrounded by vast wetlands and their unique flora among the oak woodlands and wild oats of the prairie. Stands of sycamores, willows, oak and ash formed riparian forests that stretched more than five miles beyond the banks of the Sacramento River, not to mention the myriad creeks and streams.179 Such descriptions echoed an account from Spanish explorer Gabriel Moraga’s 1808 expedition: “Canopies of oaks and cottonwoods, many festooned with grapevines, overhung the blue current. Birds chattered in the trees and big fish darted through the pellucid depths.” The members of the expedition “drank in the beauty around them.”180

One historian noted that an abundance of fauna prospered in these riparian habitats with numbers and diversity “unsurpassed in any region in North America.”181 William Davis, the captain of Johann Sutter’s ship Isabella, observed upon their arrival in 1839 that “a large number of deer, elk and other animals of the plains were startled, running to and fro, while from the interior of the adjacent woods the howls of wolves and coyotes filled the air, and immense flocks of waterfowl flew wildly about the camp.”182

|

The “boosterism” reached an apex in 1888 with this grand declaration by the chamber of commerce: “The Valley of Sacramento is a garden and Sacramento is the urbs in horto [city in a garden] of it. It is our first glimpse of the celestial flowering kingdom of the Christian world.”183 Enthralled with this evangelism, migrants from the American Midwest and South, particularly after the Civil War, snapped up real estate and established ranches throughout the region.

The notion of the Sacramento region as an agrarian paradise, hyperbolic as it may seem, does have some basis in fact. One chamber of commerce publication noted the area’s superior Mediterranean climate: Sacramento “had both sacred and beautiful soil and perfect climate, superior even to idyllic Italy’s average temperature of sixty degrees and two hundred twenty clear days with its own average temperature of sixty-one degrees and two hundred thirty-eight clear days.”184

Sacramento indeed lies in the center of the California Floristic Province, one of the planet’s “hot zones” of plant biodiversity. Over five thousand species of flora live in this zone, which stretches from southern Oregon to northern Baja California. And over one-fourth of these species exist in a relatively small number of square miles that surround the foothill sections north of El Dorado Hills.185 Perhaps unknowingly, these civic propagandists were on to something.

Even though Sacramento’s business and civic leaders took great pains to paint an idyllic natural landscape for prospective landowners, there was another side of this coin. For them, the more relevant aspect of this “rural ideal” was nature’s subservience to human will and domination. In contrast to the Native Americans, who had lived harmoniously with their natural surroundings for centuries, California’s natural resources, in the settlers’ view, demanded exploitation.

By the 1860s, the miners of the gold rush had already dredged and excavated much of the landscape. Now the abundant soil begged to be tilled and planted and the water reclaimed. Over the ensuing decades, large swaths of intensive farming developed, from row crops in the Delta to the fruit orchards of the eastern valley. What remained of the valley’s expansive riparian forests was soon lost to “the march of reclamation.”186

A central tenet of the romantic spirit was hero worship. Readers were always looking for a good story, and the exploits of early trailblazers such as Kit Carson and the tragedy of the Donner family captured the imagination of Americans and the outside world. James Beckwourth, who established the northern passage that traversed the Sierra from Nevada to Marysville, wrote an autobiography that became a bestseller in Europe.

An eager public gobbled up the latest exploits of other colorful California characters, from the outlandish stage performer Lola Montez to the miners and gamblers chronicled by Bret Harte. Now, with the late 1800s rolling along and the gold rush a memory, Sacramento’s civic leaders saw a new era at hand. It was now time for a new chapter to be written, one that has the “heroic farmer” taking his rightful place in the heart of this “vast agricultural empire.”

Yet there was more to this story. At the turn of the twentieth century, the “agriopolis” of Sacramento and its agriculture-centric suburbs, or the so-called “agriburbs” of Orangevale, Fair Oaks and Citrus Heights, formed, in their view, a small but “bustling metropolis.”187 Civic leaders extolled Sacramento as a hub of transportation, with the transcontinental railroad, an inland port and a web of transnational and trans-valley roadways.

Throw in its status as the state capital, they maintained, and there was unlimited potential for commerce and, in turn, cultural life. Sacramento offered the urbanity of town with the bounty of country and, in this way, was superior to other California cities such as San Francisco and Los Angeles.

With this origin story in mind, Sacramentans were primed, and perhaps even felt some pressure, to take on the Roosevelt administration’s Food for Victory program. The goal was simple: every home should maintain a vegetable garden, and every available open space should have a plot. Public schools and colleges, the press and business community and most notably, the University of California, all enthusiastically supported this endeavor, appealing to local patriotism and creating an atmosphere of community engagement.

By war’s end, the victory garden program proved to be one of the city’s most successful civic endeavors with Sacramento standing out as a national leader. Even more significant, the home gardening effort of the 1940s stood in juxtaposition to the increasing industrialization of the modern farm. It also offered a blueprint for today’s burgeoning “farm to fork” and community gardening movement.

|

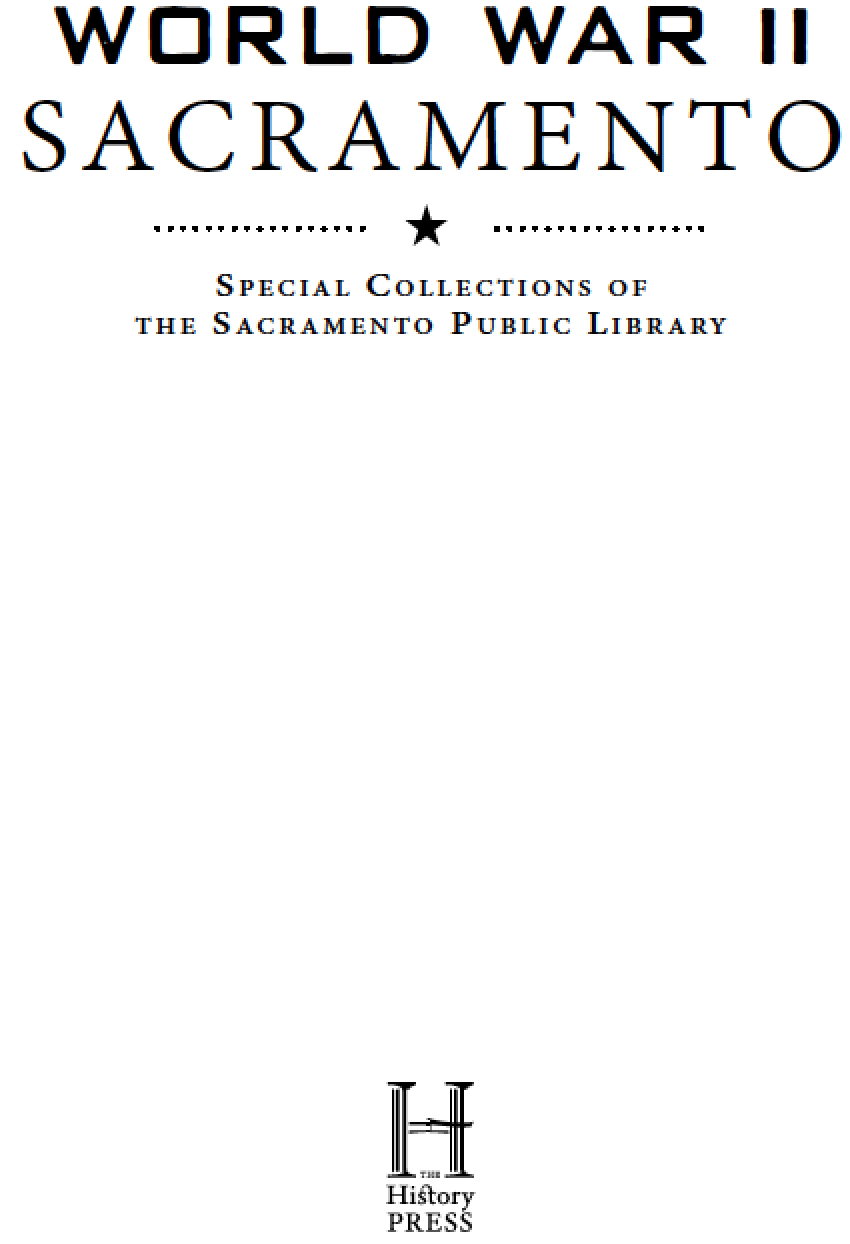

This Chamber of Commerce “War Emergency Proclamation” implored citizens to maintain victory gardens and work in the canneries. Sacramento Public Library.

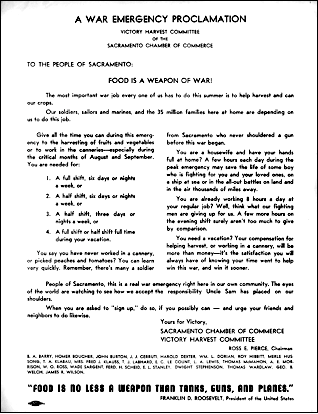

If Sacramento’s powerful local agricultural ideology provided the aesthetic motivation, rationing offered the practical incentive. Food rationing during World War II largely followed the point-based paradigm used in the United Kingdom. War Ration Book One — also known as the “Sugar Book” — was issued in May 1942. Sugar, which was the first commodity subject to restriction, was apportioned to half a pound per person per week, roughly halving the average American’s consumption. Special allowances were made for certain households that demonstrated a significant output of fruit and vegetable preserves. This proved particularly advantageous for Sacramentans, who had maintained a long tradition of producing these homemade products. Canneries, most notably Bercut-Richards, solicited residents to drop off their extras to assist in the war effort. Out in the fields, increased sugar beet acreage helped fill the deficiency.188

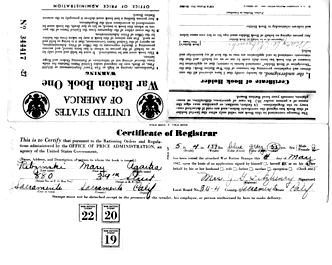

In January 1943, the point-based rationing system expanded to include stamps for processed vegetables and fruits as well as juice. Each product was assessed a point value based on type and quantity. Individuals were then given booklets that allotted forty-eight points per rationing period. A certain flexibility was allowed: stamps could be traded and products exchanged, households could combine individual booklets and stamps earmarked for a subsequent period could be used at the end of a previous one. Just as with postage, authorities encouraged citizens to use their larger denominations first so that smaller values could be used to gap purchase prices later.189

Rations also were imposed on meat. Children younger than six were allowed three-quarters of a pound per week; those nine to twelve one and a half pounds; and those older than twelve were granted two and a half pounds. Strategies such as having the occasional “meatless day” were suggested. Most typical, however, were the plethora of recipes that either offered a “meat alternative” or the less-appetizing “meat extender.”

Some of the alternative — or better put, vegetarian — recipes ranged from “Tomato Rabbit,” which actually did not contain any rabbit but was, in fact, creamed vegetables and eggs over toast, to a very simple soybean salad. The so-called meat extender recipes were, after an initial glance, quite decent, offering such staples as “Meat Pie with Catsup Biscuits” and the inevitable “Meat and Bean Loaf.”

Organ meats also were encouraged and featured in such delectable entrées as “Stuffed Hearts” and “Liver Loaf.” Finally, there were dishes only a zombie could love, such as “Breaded Brains,” “Creamed Brains” and the requisite “Scrambled Eggs with Brains.”190

|

Issued in 1942, War Ration Book One was also known as the “Sugar Book.” Sacramento Public Library.

|

War Ration Book Two, which was released in 1943, restricted canned fruits, vegetables and juice. Sacramento Public Library.

While farm tools and power equipment were rationed due to metal shortages, the Roosevelt administration had the foresight to leave basic gardening tools unrestricted. Since large-scale agriculture production was set aside for troops and allies, Sacramentans, armed with their instruments, started digging up their front and back yards. Civic leaders consistently reminded citizens that fresh produce from the home was not only good for the country; it was good for them, too. “Grow vitamins at your kitchen door” was a common refrain.191

The University of California-Davis School of Agriculture, with the assistance of the local press, embarked on a comprehensive public education campaign right after the Pearl Harbor attack in December 1941. Elmer Stanley, the county agent for the University of California and Ferd Scheid, the Sacramento County Home Food Production manager, led the effort and were ubiquitous figures throughout the war.

Stanley immediately hosted a weekly victory garden broadcast on radio station KFBK that lasted throughout the conflict, and both he and Scheid conducted and oversaw hundreds of meetings in Sacramento. By March

1942, the UC Davis Agricultural Extension had ramped up its printing press producing thousands of brochures promoting the Food for Victory program.192

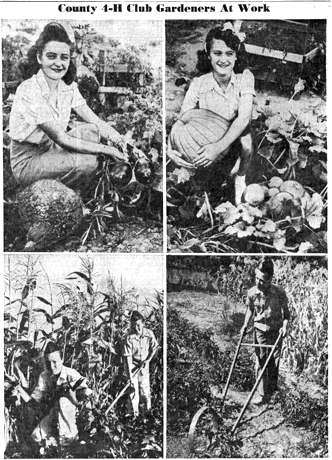

Virtually every civic organization could be counted on for an informational session. UC Davis representatives held classes for civic stalwarts such as the Elks Club, the chamber of commerce, Boy Scouts and Girls Scouts and 4-H clubs. The Sacramento Garden Club, as well as the Sacramento Fuchsia Club, saw fit to join the act, and the Sacramento High School Faculty Wives Club entertained seminars. Even an occasional informal neighborhood meeting was held in a private residence.193

For older Sacramento residents, many of whom had come from the Dust Bowl and the South, tending a home vegetable plot was second nature, reminiscent of the Edwardian farms of yesteryear. Nonetheless, as most adults were called to perform war work, it fell upon the public schools to reacquaint their children with basic gardening practices.

If not called up for military duty, many adults filled positions in civil defense. Women in particular could be found signing on for work at the bustling canneries such as Libby-McNeil, Del Monte and Bercut-Richards. As a result, the youth of Sacramento enjoyed a featured role in the victory garden program.

The greatest impact of the informational campaign was found in the alliance between the UC Davis Agricultural Extension and the region’s educational institutions. The university implemented curricula in every public school and initiated course offerings at Sacramento Junior College.

|

In November 1942, the Munz sisters tend the Fruitridge 4-H garden, and the Mohr brothers of Elk Grove work on the Franklin 4-H farm while James Broadley plows the land in Fair Oaks. All of these farms provided food for neighborhood families. Center for Sacramento History.

Schools also served as settings for seminars intended for the general public. One representative course was held in January 1943 on the campus of Sacramento Junior College. Sponsored by the state Department of Agriculture and the University of California, this six-week class covered the basics of home gardening and was attended by 150 adults.194 Dozens of similar gardening courses were tendered during the wartime era.

The Sacramento Public Library also got into the act. It offered “up to the minute” instructions on victory gardening. A wide array of books and pamphlets were provided, leading one patron to exclaim, “We’re glad to know that you don’t have to be a green thumb to be a good gardener.”195

Efforts to reclaim land for vegetable and fruit gardening got off the ground in early 1942. Sacramento mayor Tom Monk declared a citywide “Clean Up and Plant” week that started on April 13. Residents began plowing and planting in earnest. Plots sprung up at residences, and a vegetable garden was immediately sown at McClatchy High School. Sacramento High School quickly followed and ultimately had two hundred individual student sections.

With seed brought in from area farms, every public school in the city, and most in the county, had some type of vegetable garden by the end of the year.196 In that same month of April, 80 percent of the county’s ranches also maintained a victory garden as a sign of solidarity.197

In November 1942, the City Parks Department opted to include victory gardens in every city park. Mentored by the Elks Club, hordes of students immediately descended upon McClatchy, Land and Southside Parks. East Portal and McKinley soon followed, with the smaller parks close behind. The plant science departments of the junior college and high schools, under the tutelage of the UC Davis School of Agriculture, oversaw garden maintenance in the parks throughout the city and county.198

Federal, state and county officials sought to squeeze every square inch of available land for vegetable gardens. The downtown post office maintained a plot and donated its produce to needy Sacramentans. Radishes, turnips, carrots and other staples found a home at Capitol Park, and similar crops were also grown at Sutter’s Fort.199 In August 1942, the New Helvetia subdivision off Broadway included a vegetable garden behind its 310-unit apartment complex.200

In an effort to establish community gardens, Sacramento County executive Charles Deterding took an inventory of available open space. He partnered with Carl Klein, president of the Sacramento Realtors Board, who chipped in and announced, “Sacramento realtors are making Victory Gardens part of their war activity and are seeking to plant vegetables on all vacant lots in the city.”201

|

In March 1943, Mrs. A.A. Whitaker cultivates her victory garden at 1375 Forty-Fourth Street in East Sacramento. Center for Sacramento History.

Private landowners quickly heeded the call and donated parcels to the cause. Acres of vegetables popped up at Land Park addresses such as:

|

Paul Fizer of Roseville installs racks to grow tomatoes in July 1942. Center for Sacramento History.

3216 Fourth Avenue, 1037 Ninth Avenue and the major intersection of Land Park Drive and Vallejo Way, adjacent to what is now California Middle School.202 The intersection of Eleventh and V Streets also featured a community garden. In the early spring of 1943, Ferd Scheid estimated that 50 percent of the population of Sacramento planted gardens. Within six months, participation increased to 75 percent.203

The University of California-Davis Agricultural Extension offered state-of-the-art advice not only for the agricultural community but also for the amateur gardener. Stanley consistently reminded residents that a successful garden did not require a large section of land. An area measuring twenty feet by twenty feet against a back fence would do.

Yellow tomatoes, for example, could be grown on one side, lima beans on the other, interspersed with a wide range of other vegetables, such as spinach and broccoli. In a wink to the organic gardener, flowers such as marigolds were recommended to stand sentry adjacent to the plot. Such borders attract beneficial insects and reduce the need for insecticides.

Occasionally, amateur gardeners did not measure up to this sage advice. One reader of Stanley’s weekly Sacramento Bee column wondered why his watermelon crop was unsuccessful. Other readers could envision Stanley biting his lower lip as he politely indicated that watermelons were probably not best suited for a narrow strip of soil next to a driveway. After lauding the reader for attempting to cultivate such a small parcel, he went on to suggest that radishes or onions would probably be a better bet.204

Victory gardens spilled into other areas of popular culture. A long-running and popular Sacramento Bee column, authored by the pseudonymous Katherine Kitchen, offered seasonally appropriate recipes that featured common produce from home gardens. So, in spring, one might come across recipes for the simple “Stuffed Eggplant.” In

summer, “Vegetable Fritters” were on the menu, as well as the inviting “Beer Casserole.”205 During fall, recipes for “Nut Bread” and “Pecan and Rice Loaf ” were on the docket.206

The Katherine Kitchen column also delivered advice on canning vegetables and preserving fruit, including a free brochure for those who sent in a stamped envelope or attended one of the informational sessions throughout the area.

It comes as no surprise that gardening establishments, such as Lagomarsino’s Seed Store, and the East Lawn and Capital Nurseries, benefited mightily from the Food for Victory program. Yet other retailers also sought to cash in. The venerable department store Weinstock/Lubin merchandised what could be called “Victory Garden kitsch.” Displays of fashionable garden tools and paraphernalia adorned the downtown establishment.

|

The department store also introduced a smart, fashion-forward denim onesie geared toward young ladies aged seven to fourteen. Suitable for work in the garden, this particular garment highlighted the importance of young women in this civic movement.207

A good community program requires healthy competition. Foreshadowing larger events to come, a number of victory garden contests sprang up in 1942 and 1943. The Tuesday Club of Sacramento held an annual “miniature” victory garden contest that featured prizes and a lecture by Elmer Stanley. California state employees also held an annual garden competition.

Most prominent, though, was the chamber of commerce garden contest. Residents competed based on size of plot, ranging from small parcels of less than one thousand square feet to larger gardens of more than two thousand square feet. The June 1942 contest had winners such as W.E. Perry of 4464 H Street in East Sacramento and W.W. Workman of 1851 Seventh Avenue in Land Park. The contest also included a school division, with Tahoe and El Dorado Elementary Schools coming out on top.208

|

This page: Victory Garden displays were a common sight at the Weinstock/Lubin department store. Center for Sacramento History.

|

With all systems humming, one peculiar headwind arose. Along the Del Paso corridor in North Sacramento, as well as a couple of neighborhoods in the southern area of the city, packs of stray dogs harassed residents. Complicating matters was their fondness for digging. Sacramento city manager Elton Sherwin noted, “City officials have received a large number of complaints from Sacramentans who are cultivating Victory Gardens that dogs are destroying their crops.” Frustrated residents “indicated that if the annoyance continues they will kill the offending animals.”209

County executive Charles Deterding jumped on the case and found that Fairfield had a similar problem and had implemented a series of traps to capture the fugitive canines. Corresponding measures were enforced in Sacramento, with apprehended dogs sent to the pound. Fortunately, the majority of them were reunited with their owners since the dogs were licensed. Sherwin wagged his finger at residents, complaining that “even though a $1 permit has been obtained for a dog does not mean the animal can run loose.”210

The stray canine issue ultimately proved to be a minor annoyance, and these initial efforts began to pay off. According to the annual UC Davis county agriculture report for 1942, twenty-five thousand home gardens were established. In addition, there were four thousand home poultry flocks, four hundred rabbit hutches and two hundred additional herds of cattle in Sacramento County.211

With momentum on its side, Sacramento brought out the heavy hitters to promote the Food for Victory program. McClatchy empire stalwarts, KFBK radio and the Sacramento Bee, as well as the county Department of Agriculture and the University of California, sponsored an annual harvest festival. Held at the Memorial Auditorium, it occurred on the first weekend of August from 1943 to 1945.

With the state fair on hiatus during the war, the three festivals met pent-up demand and averaged an overflow crowd of fourteen thousand. Enticed with music, contests, prizes and patriotic appeals, Sacramentans flocked to the Memorial, creating one of the best attended series of non-sporting events in city history.

In July 1943, the County Board of Supervisors signed on to support the festival. Days later, Governor Earl Warren, who had started his own garden at the governor’s mansion, unleashed a gleeful challenge to the county’s victory gardeners, which by now had numbered thirty thousand: “You can count on a display of vegetables from the Warren Victory Garden and I’ll say right now that if any of the products of Sacramento gardens can taste any better than those we are now harvesting from our garden, they are entitled to a prize.”

On a more serious note, Governor Warren went on:

It is my hope that the Sacramento Victory Garden festival will provide inspiration and knowledge causing thousands more home owners in the area to plan fall and winter gardens. During the year one-fourth of our total food products will be required by our armed forces and our allies. This demand plus the labor problems which have arisen in many farming areas makes Victory Gardening both a patriotic duty and an economic necessity. Certainly it is a prudent precaution for every family with space available for ordinary vegetables and greens. You can count on me to lend encouragement to any program which will give emphasis in the desirability of Victory Gardening.212

The head of the California Department of Agriculture, Merle Hussong, added a stark humanitarian plea in his support for the festival: “We must produce food for the 500,000,000 starving victims of Axis aggression who must be fed both now and after the Allies have achieved victory.”213

With the governor’s marching orders in hand, volunteers opened the doors for the inaugural Victory Garden Harvest Festival at 1:00 p.m. on August 5, 1943. The Emil Martin orchestra greeted the crowd and played big band hits throughout the two-day affair with a collection of “prominent” military performers rotating through the sets.

While the band performed on the main stage, about one hundred Girl Scouts escorted onlookers as they surveyed the various entries scattered on tables throughout the main auditorium floor. The hours of 2:30-5:00 p.m. and 5:30-7:00 p.m. were set aside for informational lectures and short films in the adjacent Little Theater.

Underlining the ultimate goal of the event, however, were one hundred representatives from local garden clubs and the University of California-Davis School of Agriculture who gave out advice throughout the festival. The formal starting ceremonies were held shortly after 7:00 p.m. with county Food for Victory coordinator Ferd Scheid as the master of ceremonies and Mayor Tom Monk as the keynote speaker. The festivities wrapped up each day at 10:00 p.m.214

The harvest festival contest itself had a very similar format to the chamber of commerce competition. In the days prior to the event, judges fanned out to local victory garden participants in the area. With coveted war bonds and war stamps as the incentive, entrants were rated based on presentation, crop yield and ingenuity of garden technique.

|

This is a 1941 photograph of the parcel where Governor Earl Warren and family planted their victory garden. The Governor’s Mansion is in the background to the left. Center for Sacramento History.

Just as with the chamber competition, categories were based on lot size: small (less than 500 square feet), medium (less than 1,500 square feet) and large, with some of the biggest residential lots exceeding 5,000 square feet. The community garden category had no limit on square footage.

Meanwhile, inside the auditorium, judging took place in the individual vegetable, fruit and display categories. Attendees ogled the various entries as they navigated their way through the building. There was, of course, the mandatory “largest watermelon” category, but every fruit and vegetable was judged, not only on size but also on the more important qualities of taste and appearance, with the more exotic entries having the best chance at winning a prize.

Displays of every incarnation, from vegetable bouquets to fruit poster boards, came from all corners of the region. Along with residential participants, Sutter’s Fort and Capitol Park as well as the city schools and parks entered the fray. Preserved fruits and vegetables were the largest category of the competition. Ultimately, all of the submitted jars and cans were given to the Bercut-Richards cannery and were distributed with the signature “V” label.215

At the 1944 festival, one winning entrant tested the bounds of imagination. In an homage to the dreaded and ubiquitous garden pest, a competitor constructed a large, menacing insect out of fruit and vegetables. The thorax consisted of a zucchini, the legs rhubarb. The creature possessed eyes made of red berries, a green berry mane and ears of succulent leaves. A nifty white bow tie topped off the costume. By all accounts, this dapper monstrosity was the star of the pageant.216

After the initial 1943 harvest festival, KFBK and the Sacramento Bee decided to take their marketing efforts a step further by producing a film that both promoted the next year’s edition as well as victory gardening in general. This thirty-eight-minute silent film, which used intertitles to convey scene changes and information, was shot and directed by Sacramento Bee photographer Harry Handsaker.

The movie became a local classic in spite of the fact that it was Handsaker’s first attempt at filmmaking. Handsaker recorded the documentary in color on 16mm film, and since he did not have post-production editing facilities, he edited it on his camera.217 The movie consisted of two parts, the latter featuring scenes of the 1943 festival.

The first part of the film is particularly noteworthy in that it features a local telephone linesman, Prentiss Ferguson, and his wife, daughter and son at their residence across from Land Park. Mr. and Mrs. Victory Gardeners, as they were called, were shown planting, irrigating and otherwise tending their home garden on Seventh Avenue.218

This section of the movie also featured the gardening efforts of Ferguson’s neighbors both at home and in the community.219 The film debuted at the KFBK studios and then made the rounds throughout 1944 and 1945, showing at community centers and movie theaters, including the Alhambra and the Little Theater at the Memorial, and at every conceivable meeting hall.220

Anticipation and uncertainty filled the air as the last harvest festival opened its doors once again at 1:00 p.m. on Saturday, August 4, 1945. Along with the rest of the United States and its allies, Sacramento had celebrated the surrender of Nazi Germany on May 8. The slog continued in the Pacific, however, but significant gains had been made: the fall of Iwo Jima in March, the British conquest of Burma in early May and the American takeover of Okinawa in June. The demise of Imperial Japan seemed imminent, so much so that the Allies demanded unconditional surrender at the Potsdam conference on July 27. But Tokyo refused, and the fighting continued.221

The festival had a similar format as in years past but this time carried a “country fair” theme. F.M. Sandusky, the newly appointed head of the California State Fair, presided over the festivities, which included more than one thousand exhibits “ranging from cucumber and tomatoes to canned string beans and currant jelly.”222

Katherine Kitchen, the Bee’s resident home economist, set up shop on the west side of the auditorium foyer just as she had done in years past. At her desk, Kitchen distributed literature and “consulted on nutrition problems,” and on the floor of the auditorium, she offered wisdom in “the home preservation section.” In another corner of the auditorium, the university extension displayed the latest in home refrigeration.223

On the second day of the festival, at 4:00 p.m. on Sunday, August 5, about three thousand festival-goers were enjoying the last hours of the event. As usual, the strains of Emil Martin’s big band filled the hall as attendees milled about the exhibits. Others crammed the adjacent Little Theater, watching one of the many instructional films on home gardening. As people were taking notes and perusing the displays of rhubarb, broccoli and asparagus, the “Enola Gay” dropped the atomic bomb. Hiroshima lay in ruins.

The next twenty-four hours produced a news cycle that local editors would never forget. Not only did news of Hiroshima break that evening on the radio and the next day in the Sacramento Union and Bee, yet another story, one of particular significance for Sacramentans, broke as well. At 6:45 a.m. on Monday, August 6, Hiram Johnson, native son, former California governor and current U.S. senator, died of a stroke at Bethesda Naval Hospital.224

Johnson’s death, which was not entirely unexpected since he had been in a coma for a couple of weeks, had a ring of irony. On one hand, he had expanded certain rights and battled corruption as a Progressive Era champion. As governor, he helped bring the franchise to women, established the initiative, referendum and recall process, regulated public utilities and the railroad and instituted labor reforms. But he also possessed an antipathy for East Asians, most notably the Chinese and Japanese, and will be remembered for his relentless quest to restrict their immigration and property rights.

After Japan signed the treaty of surrender on September 2, 1945 and the celebrations died down, locals took stock of the community’s performance in the Food for Victory program. Starting in 1943 and throughout the remainder of the war, the county had held steady with thirty thousand victory gardens. In the United States, approximately 80 percent of residences maintained a plot and about 40 percent of produce consumed came from a home or community garden. Sacramento County exceeded these averages with upwards of 90 percent of residences participating and more than half the produce grown at home or in the neighborhood. According to the state Department of Agriculture, Sacramento had one of nation’s best programs and was “the per capita leader of the west coast.”225

The harvest festivals were a sensation and reported forty-two thousand in attendance over the three years. Later in 1945, Eleanor McClatchy, the matriarch of the family media empire, received a personal letter from Eleanor Roosevelt, commending her for the harvest festivals and promoting victory gardening in general.226 Sacramento had indeed lived up to its lofty agrarian heritage.

The later years of Prentiss Ferguson, the “Mr. Victory Gardener” of the Robert Handsaker film, were fittingly emblematic of postwar America. Ferguson clearly had an interest in gardening and the environment, as records indicate his membership in the local chapter (Sacramento Valley) of the California Native Plant Society (CNPS).

Although documents prior to 1968 have been lost, it is most likely that he was one of the twenty founding members of the society at its inception in 1965. He was a thoroughly active member of CNPS, becoming its vice president in 1969 and its president in 1970.

In those and subsequent years, Ferguson led a multitude of field trips, including botanical walks, throughout the capital region.227 Sacramento’s most prominent home gardener had evolved into a familiar figure in post-1960s America — citizen scientist and environmental activist.

The current home gardening movement, including Sacramento’s claim as America’s “farm to fork” capital, has now come full circle. Just as they did in the 1940s, city and county residents can once again maintain gardens in their front and side yards and sell produce without a permit. Lists of seasonal varieties, the use of sentinel plants and other gardening advice found in the thousands of victory garden pamphlets are now codified in the University of California Master Gardener’s Manual. Photos and biographies of local organic farmers adorn produce sections in local markets just as restaurateurs who utilize this produce are featured in local and national publications. The harvest festivals at the Memorial Auditorium have morphed into the “farm to fork” festivals of today.

Indeed, the “heroic” farmers of yesteryear have not disappeared — they have merely come home. The victory gardeners ran interference for an industrial-agricultural machine that fed troops and allies and, in later years, sustained an increasingly hungry nation.

But their civic duty also offered an alternative. Ferguson and his disciples have sought to rectify some of the environmental damage done by intensive farming, to perhaps restore in some small measure the other half of the “rural ideal” trumpeted by Sacramento’s forefathers. They had taken to heart Rachel Carson’s admonition: “’The control of nature’ is a phrase conceived in arrogance, born of the Neanderthal age of biology and philosophy, when it was supposed that nature exists for the convenience of man.”228

But now the stakes are even higher. The home gardeners of today and those of World War II share one last and most important trait: an enemy. For the victory gardeners of the 1940s, it was the Axis powers; for today’s home gardener there is a no less immediate and formidable foe, climate change.

Copyright © 2018 by Eric Webb